Feeding the Soul: Rehoboth’s Bob Yesbek

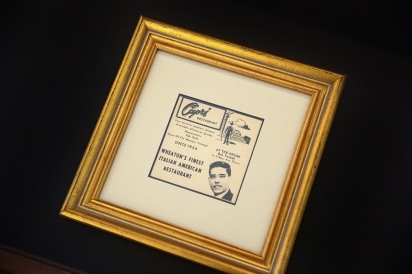

Bob Yesbek was a high school freshman when he learned to spot an opportunity. The young musician realized that the Hammond Organ Studio was across the street from the Capri Restaurant, his parents’ favorite Italian eatery in Wheaton, Maryland.

The fresh-faced teenager approached restaurant owner Frank Passero. If the music store would put a loaner in the dining room, would Passero let Yesbek play? Passero agreed. Yesbek would earn only a few dollars per hour but could eat his fill of pizza and pasta.

From 6 p.m. to 9 p.m., Monday through Thursday, Yesbek dutifully sat at the keyboard, playing standards popular in the late 1950s and early 1960s. And during every break, he ordered another dish — or two — from the kitchen. Finally, Passero put his foot down. “He’s eating me out of house and home!” he told Yesbek’s father.

“It was my first restaurant gig, and I almost got fired,” recalls Yesbek. Although Passero put a kibosh on the free meals, he gave the performer a raise.

So began the happy marriage of Yesbek’s twin passions: music and food. Over the next 50 years, he’s spent untold hours at the keyboard, mixing board, and cutting board. He’s owned radio stations and restaurants. Now known as the “Rehoboth Foodie,” Yesbek is a coastal Delaware food writer, radio personality and, more recently, the leader of 2nd Time Around, a classic rock trio.

He is the poster child for the expression: “Do what you love.” And he still uses his ambition and ingenuity to create symbiotic relationships between all these endeavors.

An Early Start

Yesbek and sister Cathy grew up in the Washington, D.C., area. Their father, William Robert Yesbek, was a dentist of Lebanese descent; his parents had left Beirut to open a restaurant in downtown D.C.

During World War II, Dr. Yesbek met Clota Mae Damron, a Texan. His family was not pleased. “She was considered an outsider,” Yesbek says. “They taught her how to make Middle Eastern food, and since she had no issue with deep-frying — she was a very good Southern cook — she improved on their recipes, which annoyed them even more.”

His mother’s recipes form the foundation for his award-winning fried chicken and his no-bean

Texas chili. (Her chili was better thanks to suet, but “even I can’t do that,” says Yesbek, who can seemingly eat his weight in cholesterol-rich dishes.) He also makes a mean tabbouleh.

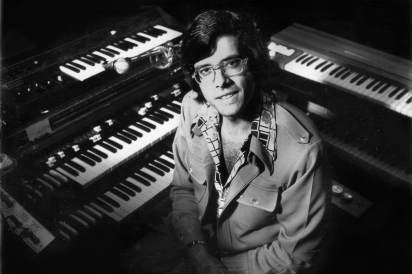

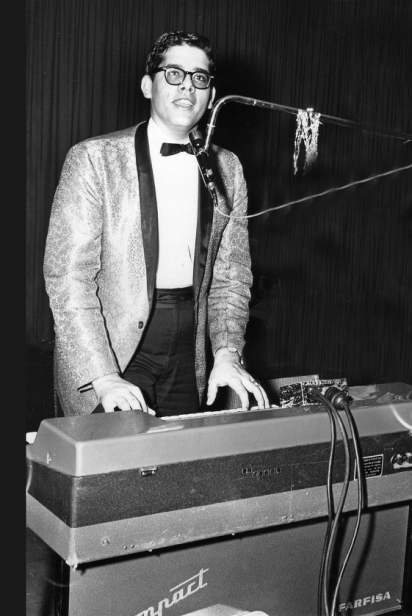

Yesbek took piano lessons from a nun, who was also a teacher at his Catholic elementary school. During class, Yesbek played the rickety pump organ while the children sang hymns. He switched to the organ in the 1960s when the Farfisa and Hammond B3 formed rock’s signature sound. By age 12, he had a mini-recording studio in his bedroom.

The Hi-Notes, a five-piece band, formed in 1964 when Yesbek was a high school sophomore. They played the local dances at area venues. When the musicians were old enough, they began playing rock clubs in downtown D.C., including The Keg and The Bayou. “We even opened up for name acts at American University and the University of Maryland, including Vanilla Fudge,” Yesbek says. If the location had a kitchen, he’d be in there between sets. “I watched the cooks do this and that,” he says. “I was learning, asking questions.”

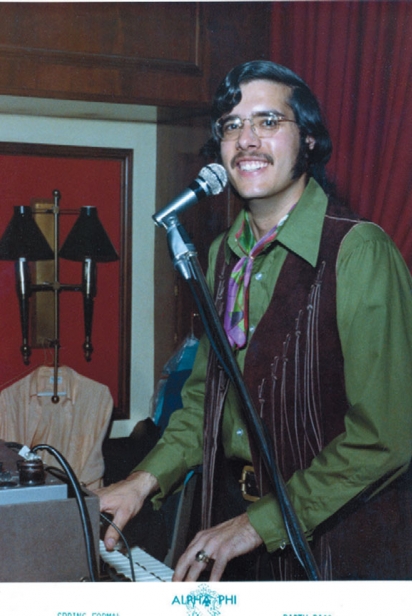

In 1968, the Hi-Notes played a New Year’s Eve gig at Hideaway Lounge at the Stowaway Motel in Ocean City. The owners liked what they heard, and the band wound up playing full time for two summers and on weekends over three winters.

As the dancers gyrated to Creedence Clearwater Revival, Yesbek tossed back the dark hair that fell to the waist of his bellbottoms. “I could take five steps and the pants wouldn’t move,” he says of their width.

Like The Monkees, the group lived together on the bay near 72nd Street. Yesbek, a student then at the University of Maryland, commuted between OC and school. “I used to study my book while driving,” he says. “It’s a wonder I’m alive.”

Turning up the Volume

In the early 1970s, Yesbek opened Omega Studios in Kensington, Maryland. At the time, he was in med school, but business did so well — there were up to 40 employees — that he converted his studies to a master’s degree in the second year. “I could not do both anymore,” he says. “It was the best decision I ever made.”

He purchased other studios, more equipment and recorded some of the top names in the business: Barry Manilow, Prince, Elton John and The Pointer Sisters. To boost production work, he bought radio stations in Florida. But when the recording studio — which he had consolidated in Rockville — demanded more time, he sold the stations.

The band, meanwhile, kept morphing. The musicians traded their bell bottoms for wide-lapeled leisure suits and rock clubs for lounges. But when Yesbek opened a professional recording school, the Hi-Notes fell flat. “I was going crazy,” he says. “I was the only one who could teach the technical classes.”

In 1992, Yesbek sold Omega, although he stayed on to help.

An Appetite for Entrepreneurism

Eager to explore new paths, Yesbek became an investor in an Italian sub shop and then Fleetwood’s, a blues club and restaurant in Alexandria. The Cajun-Creole concept’s name paid homage to partner Mick Fleetwood, the drummer for Fleetwood Mac.

“He wanted a fully professional sound system — like a recording studio,” Yesbek recalls. With hundreds of seats and a gigantic kitchen, the restaurant was challenging to operate. Plus, Mick Fleetwood didn’t visit as often as the guests expected. It closed a few years later.

Yesbek then concentrated on one of his favorite cuisines: barbecue. Ten Star Fire Company opened in Bethesda, Maryland. He quickly gained an appreciation for the labor required to run a restaurant. However, it became too much for a man with retirement on his mind.

In 2002, it was time to move to the beach, where he’d vacationed since he was a child. In his Rehoboth home, he noodled on the Hammond B3 now and again, but his performing days were over. Or, so he thought.

Second — and Third — Careers

Retirement was not in the cards. Yesbek started RehobothFoodie.com to comment on the local restaurant scene and created an app, Rehoboth in My Pocket.

One thing led to another. Yesbek became a columnist for the Cape Gazette, wrote articles for other publications, and started Eating Rehoboth, a walking tour, with friends Paul Cullen and Deb Griffin. He got back behind the mic with Sip & Bite, a radio show about the hospitality industry, which he initially launched on Delaware 105.9. The show recently moved to WGMD 92.7.

But he had yet to return to his musical roots. That changed in 2017 when he watched a jazz trio perform during the True Blue Jazz Festival. “I listened to the band and said: ‘I can do that. There’s nothing here that’s a mystery.’”

He began practicing with area musicians, and the first appearance of 2nd Time Around was before a packed house at The Cultured Pearl in Rehoboth Beach. He quickly booked gigs at The Pond, Bethany Blues and Irish Eyes, all known for music. “Once he played a few times, I think even he was surprised” at the reaction, says Kevin Roberts, a partner at Bethany Blues.

Thanks to Yesbek’s contacts, the band has also played at unconventional spots, such as Touch of Italy, Indigo — an Indian restaurant — and Fork + Flask. “His connections with musicians and restaurant people exceed those of most people,” Roberts says.

Yesbek, who wears a glowing skeleton sock to play the foot pedals, is having the time of his life. “It’s a lot of fun for him, and it’s another outlet,” Roberts says. “He’s a social person, and what’s more social than playing music with other musicians for others?”

Pete Borsari, owner of The Pond, agreed. “He just loves bringing joy to people, and he can really do that with music.”

During Delaware’s state of emergency, the band live-streamed from The Pond to raise money for out-of-work servers. Between his radio show, app, column and website, Yesbek remained busy even when restaurants were limited to carryout.

He’s also become an outspoken advocate for the industry. “When a restaurant closes, it can be due to any number of factors — including just getting tired and walking away,” he notes. “But the next time I hear somebody say they never go downtown or don’t want to walk a few blocks to a restaurant; I might suggest they refrain from shedding crocodile tears over a place they never saw fit to visit.”

You can be sure that Yesbek, who tips generously on carryout, always puts his money — and his pen — where his mouth is.

Keep up with Bob at The Rehoboth Foodie and on Facebook