Friendship, Communion, Food: Waterfowl at the Chesapeake Winter Table

An inextricable part of the winter landscape on the Eastern Shore is the waterfowl. Thousands of them like cyclones, circling above wide-open fields. Their din is a roar of woodwinds, a startled cacophony of swans, geese and ducks. As these migratory visitors move twice daily, from the fodder of the fields to river coves, their straggling V’s define the cold months here as much as the temperature.

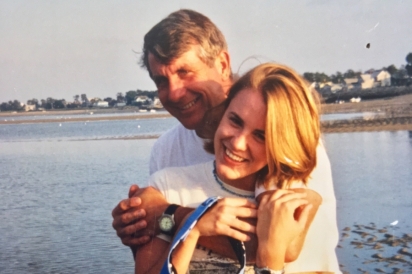

Since I was a very little girl, these waterfowl have been as much a feature of my tablescape as my landscape. My father was an ardent, lifelong sportsman who counted down the months, days and weeks each year to goose and duck season. We ate his harvest—Canada geese, canvasbacks, redheads and mallards—all winter long. While my friends sat down to family dinners of pot roast or fish sticks, my sister and I hovered greedily at the cutting board, waiting for the knife to reveal the glorious, tender pink inside the char of a grilled goose breast. Whatever was left (there was never much) was packed by into a brown bag for lunch the next day by my single dad. One thing is for sure—you’ve never truly experienced middle school until you’ve gnawed a goose leg, Neanderthal-like, in front of a crowd of stunned Lunchable eaters.

My dad’s love of waterfowling might not have made me many friends, but it definitely created deep connections for him, both in the blind and at the table. Hunting forges a special kind of camaraderie. Created by bitterly cold mornings spent painstakingly arranging your decoy rig, patching holes in your waders with duct tape, and sitting and shooting the breeze while waiting for signs of incoming birds, it was a sport that tended to draw kindred, hardy spirits. These guys weren’t just hunting buddies—they were men cut from the same cloth. Sportsmen who respected the birds they shot and the art of pursuing them, who ate their take with reverence and gusto. In the blind, they were brothers—a friendship and connection that ran as deep as the Chesapeake, locked up under a rime of ice.

You could tell because the conversation never stopped once the day’s limit was reached. The party just moved from the blind back to the house. It continued as my father and his friends—collectively known as ‘the guys’—cleaned their birds and breasted them out, errant puffs of down clinging to their hair. The day’s hunting adventures or misfortunes were recounted back in the kitchen while the men leaned on counters. Scotch was poured into tumblers and birds brined. Somehow all of my dad’s hunting friends were also fabulous cooks. They sustained their banter while adding cognac and cream to an au poivre reduction or tossing wafers of smoky sausage into the cassoulet’s simmering beans and duck confit. It wasn’t until the dishes were scraped clean and the wine glasses drunk down that they sat back in silence, stunned by food and exhausted by their 3 AM wake up call. My sister and I, pressed in on both sides at the table by these warm men in layers of flannel and long underwear, just listened. Full and drowsing under the last rumblings of conversation, we felt safe.

In these close, crowded kitchens, lit by drippy tapers, those dishes of waterfowl felt like a sacrament. The savoring of the Bay’s very body, these were birds sustained by the river’s bottom grasses and sheltered in frosty marshes. Each had been harvested with skill, appreciation, and restraint. My father, an agnostic for most of my life, often remarked that time in the field, for him, was his version of church. In that analogy, I think those meals were like the chorus—raising voices in thanks for this manna, this fellowship of birds.

My father is gone now—he died when I was in my 20’s and just beginning to understand the part of me that was really him—gifting me his love of the Chesapeake and its sense of place. But I still have those wonderful friends of his in my life—and their recipes—to remind me of him and those glowing, beautiful evenings around the winter table. So much more than meals, they were a winter communion celebrating the joy of hunting, friendship and a damn fine dinner.