Grieving in the Kitchen

I received the phone call on a warm Sunday in May.

“Can I talk to mom?” my sister asked.

I took a deep breath. This was going to be bad news.

“Yes,” I said, before handing the phone over.

A few weeks earlier, my mother had flown from France to help me care for my newborn. Rubbing my baby’s head, I was now waiting for her to hang up. When she did, she avoided my gaze.

“Aunt Julya died,” my mother said. She then asked for a candle to light after a prayer.

That was it, I thought, the dreaded phone call had come. A close relative had died on another continent and I wouldn’t be able to attend their funeral. I felt an odd mix of emotions: sadness, of course, but loneliness, too. I knew grieving alone was part of the immigrant package and I had spent the past five years preparing for this day. Still, I couldn’t help but feel left out.

I longed to be with my family. I wanted to cry the loss with my loved ones, then find comfort in our shared memories. I craved the tightness of their hugs and the familiar sound of their voices. I ached to feel harder, the sorrow and the love, the pain and the comfort. Together, we would have felt it all. Instead, I was home, with nowhere for my feelings to go.

I felt restless. I got up, sat down, picked a book, then put it back. I could start planning dinner, like nothing ever happened, but that didn’t feel right. Like the rest of my family, I wanted to remember Julya Arditi.

Julya was my mother’s aunt, her father’s older sister. When we visited her, Julya always wore a big smile, bigger glasses, and boldly patterned, colorful dresses. In summer, her platform sandals showcased a mesmerizing, metallic nail polish. She was a confident, easy-going lady.

In the 1970’s, when my parents left Turkey for France to start a family, they bid farewell to a tightknit group of relatives. Undeterred by the distance to their homeland, they were adamant on taking my sister and me back to Turkey “to make memories,” as my dad would say. Until my tenth birthday, when the Yugoslavian war broke out, August meant a three-day drive across Europe to the coastal city of Izmir, off the Aegean Sea. The trips not only opened us up to the world, they let us build close bonds with our Turkish family.

Of all the relatives we’d see, I liked Julya and her husband Jacques the best. One year, they invited us to their beach house for a week, filling our days with sandcastles and turquoise water. On Friday nights, my great-aunt hosted Sabbath dinner at her breezy summer home. I remember laughter-filled functions, adults chatting on the front patio and cousins shouting in the back.

Like all my family, my great-aunt Julya was a member of the Turkish Sephardic community. In 1492, when the Spanish Inquisition forced Jews to convert to Catholicism, my ancestors escaped Spain and resettled in what was then the Ottoman Empire. For the next five centuries, they continued to speak a language known as Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, and preserve their culinary traditions.

A mom of four, Julya was a practical cook who made entertaining look effortless. On those Sabbath dinners, she’d serve traditional Sephardic dishes, such as green beans stewed in olive oil, white beans simmered in tomato sauce, and leek and beef meatballs, all accompanied by a side of white rice cooked pilaf-style.

I was 24 the last time I’d seen her. By then, I’d graduated from college, moved to the United States, and was newly engaged. The summer of 2003, I’d flown to Turkey for my last vacation as a bachelorette. The photos taken during that trip show my parents beaming and my grandfather laughing. I don’t have pictures of Julya but I remember her smile had grown tired.

In the early 2000’s, when my interest in cooking was budding, my sister Sarah’s was full-fledged. With our grandmothers both gone, she would turn to Julya for clarification on our family recipes.

“How much flour do you add?” Sarah would ask, watching our great-aunt knead bread.

“Until the dough has the consistency of an earlobe,” she’d reply.

I was reminiscing that scene when it suddenly hit me.

“We should make roska,” I told my mom.

I dashed to the kitchen and dusted off my mixer.

Roska is an enriched, yeasted bread served on Sabbath and other Jewish celebrations; think of it as the Mediterranean’s answer to challah. Unlike challah, roska isn’t braided but shaped into a coil. Recipes for roska vary greatly but, to me, it should have a cinnamon-scented, cake-like crumb straddling the line between sweet and savory. My mom always raved about her aunt’s version, so she made it for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, the only time she felt like fiddling with yeast.

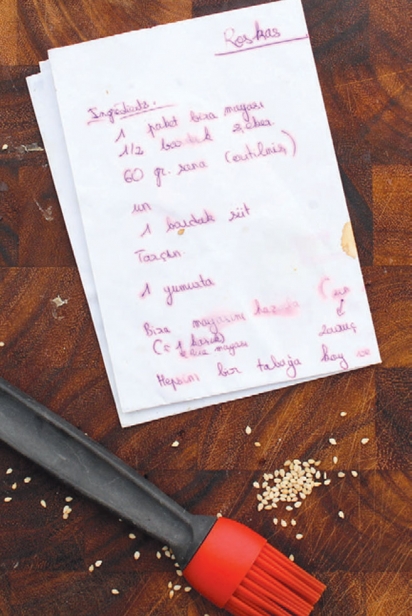

Thanks to my sister Sarah, I also had a copy of the recipe. I pulled it from a binder like a precious archive. As I gathered the ingredients, I was surprised that her roska called for milk, although it had likely accompanied meat dishes. It was in contradiction with Jewish law which forbids serving meat and dairy at the same meal. I thus concluded that Julya wasn’t too worried about keeping a Kosher kitchen, which I wasn’t either. I was less startled by her use of margarine, a popular ingredient in the 1950’s, though I chose to replace it with butter because it just tastes better.

Like most housewives of her generation, Julya often gave loose ingredient measurements, when she gave any at all. Here, she listed “flour” and “cinnamon” without any clue of how much was enough. Part of me envied her: she trusted her hands with flour in a way I never learned to. Could it ever be too late to become that kind of cook? I decided not, because I had no other choice. I took a leap of faith and followed my great-aunt’s lead by adding flour to the wet ingredients, first by the cup, then by the half cup, kneading the dough until the texture felt soft and tender like my earlobe. The indication of “cinnamon” stumped me. Most cake recipes call for a subtle teaspoon, but the dough was heavy, so I went for a bold tablespoon instead. The powdered spice tickled my nose.

“Make the dough, let it rest, shape it. Let it rest and bake.”

Those were Julya’s instructions for making bread. By then, I’d thankfully made enough loaves to settle on an oven temperature of 350° and start checking the doneness after 40 minutes.

In the kitchen, grieving was a physical process. It meant scooping flour from a bucket, mixing wet and dry ingredients, punching and shaping dough. Grieving required strength, but it needed patience, too. I waited for the dough to rise – twice – then for the round loaves to bake and cool.

I pulled the two roska loaves from the oven and presented them to my mom. This time, she looked at me and smiled.

“They look good,” she said.

At the table, we pulled the soft dough apart, letting the steam escape. The roskas were just like I remembered: barely sweet, slightly dense, with the familiar cinnamon scent that took me back to those Friday dinners. I sat back in my chair, feeling appeased. We had paid homage to Julya’s life; the time had come to let her go.