Life of the Party

Everyone has a mother. But nobody had a mother quite like mine. Robin was a force of nature. Her high spirits, charisma and sense of fun buoyed everyone around her. She loved to laugh (she had a big, room-filling laugh, the kind that made other people turn around and stare), and when I was small, she was also innately glamorous in the most quintessentially 80’s kind of way. Hot-rollered hair, long, lacquered nails, teal eyeshadow and deep pink mood lipstick she applied by placing the tube between her lips and pressing down, leaving a little spike of color behind in the stick. Mom taught me and my sisters how to flip our heads upside down, hide our eyes and noses behind a dishtowel, and draw faces on our chin so that lip-synching to Bobby Brown songs became the most hilarious entertainment ever. She was a master of the transformation—boring became riveting, quiet was made raucous, drab turned fab, and all of it seemingly came from nowhere.

Mom was a glittery sort of person. Much of this joie de vivre was drawn from people, so she was always having friends over, making occasions out of the ordinary drop-in. But her lust for life, her boundless appetite for fun had a sharp, brittle edge. It could get too big, go too far. It became mania, episodes that involved all-nighters, shopping sprees and big grand visions that came crashing down a few days or weeks later, plunging her into a dark bedroom to recover. Later we would learn she had been bipolar her whole life. It was a sensation she chased, first through experiences and later through substances. Ultimately, she and my father would split over this. Throughout my childhood, Mom would appear and disappear from my life as she struggled to manage her demons.

One of the things that always drew her back was the holidays. The epitome of all things entertaining, celebratory, traditional, decorative, and of course, transformational, she would materialize in a cloud of carols and perfume, lugging huge bags of presents and trailing a mist of sparkle and magic in her wake. Our Charlie Brown single dad Christmas tree would be overhauled in a 5th Avenue department store-style makeover, the Carpenters holiday album boomed from the stereo, and there would be cinnamon simmering on the stove — not for practical reasons, just to fill the house with the warm scent. Christmas morning itself was an orgy of presents longed for and never even imagined—big Victorian doll houses, fully furnished, animatronic teddy bears that talked and asked you questions about yourself. Mom and Dad drank coffee with brandy and for a brief sliver of time we felt like a normal family.

The pinnacle—and conclusion—of this merriment was a New Year’s Eve party, which, like everything else, Mom threw with effortless style. Hors d’oeuvre crowded the dining room table as the grown-ups mingled and sipped cocktails. We three girls watched from behind the second floor banister, wearing our special matching flannel nightgowns. We wished we could be grown-ups too, laughing and decked out in taffeta and party hair, glasses clinking, so sophisticated.

As a child, and even now, I treasure these memories because they were so rare. In my world, mothers weren’t a constant—they were a beautiful breeze that blew in and lifted away the ordinary with matching outfits for me and my sisters and toys and all sorts of happy commotion. Then, just as unexpectedly, she’d blow out again, thunderheads on the horizon and the rooms emptier, duller.

As an adult, I have struggled to reckon with the aftermath of her intermittent presence in my life, especially since her death five years ago. Am I like her? I ask myself. Do I hold the same damaged parts, that will one day make themselves known and create chaos in my world, for the people I love? Mostly, I find that I don’t share these qualities with my mother. What I do have is her creativity, her ability to set a scene and transform something from bland and cold to warm and beautiful. I’ve tried to find ways to connect with her memory, and my own.

I paint, like she used to. I arrange flowers from my own garden and fill our house with their beauty and blooms, just so. And every year (covid permitting), I throw a New Year’s Eve party of my own. I plumb the depths of a grown-up closet that holds dresses and high heels every bit as elegant as hers, and I craft an evening I hope will rival the spectacle and celebration of a Robin-hosted occasion.

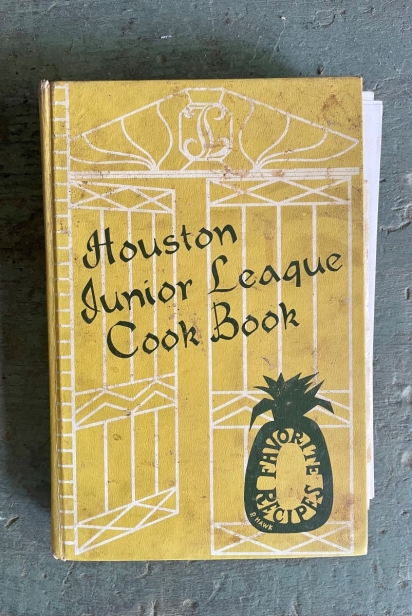

Before she died, my mother gave me a treasure that is central to all of these efforts—a stained, dog-eared, margin-marked copy of the 1978 Houston Junior League Cookbook. The recipes are analogs to similar Chesapeake ones, with even more game recipes (a good thing because my dad loved to hunt). The pages are stuffed with extra recipe cards and printed out housekeeping tips, and her handwriting everywhere makes my insides crumble. But there is an inscription, “To Kate. I hope this book serves you well as it has served me and many guests of mine. Love, Mom.” There is so much love and experience in those words, so much that is shared. They are a bridge, connecting us now, even when we tried and struggled so often to reach each other in life. Maybe it isn’t too late after all.

Every year I make her recipe for Texas Crabgrass, a hot spinach and crabmeat hors d'oeuvre she never failed to serve at a party. She always had to have reserves in the wings, it went so fast. She made it her own with a few special twists—a dash of Worcestershire sauce, a sprinkling of Old Bay—so now I think of it as Chesapeake Crabgrass. I always use real Maryland crabmeat because I am not some chickennecker. It is creamy and green and sweet with the crabmeat, and smeared on crackers it is the perfect thing to hold in one hand while the other pinches the stem of a glass of champagne. It is the ultimate party food.

Relationships are complex between mothers and daughters. We want to be just like them, we want to define ourselves as different, we want to do it the same, even better, we don’t want them to tell us what to do. But we yearn for each other, no matter the water under the bridge. Those dark winter nights, when my friends crowd around me and we celebrate the end of another year together, I feel her nearby. She would be the one with high spirits cracking jokes and turning up the music to dance, making you dance with her too, no matter how much you protested. And you’d like it. My little dish on the dining room table, her signature staple, is an offering, a little shrine. From the white tablecloth, it is a thread of welcome saying, come on in. The candles are lit. The party’s here, and you’re all invited.