Making Merry in Maryland

Right after Thanksgiving, the bottles start showing up. Mason jars, empty wine bottles with handwritten labels that let you know whose family recipe this is. You’re sent home from parties with them or given the 2022 batch as a gift—boozy homemade eggnog that will last so much longer in your refrigerator than you ever thought possible. It’s a traditional staple most of us never really think about, as mainstream as holiday foods get. But eggnog is a curious thing. It’s not just old school, it’s old—18th century at least. And it’s not the only holiday food that is. Amazingly, many of our classic Christmas recipes are foods and drinks we have enjoyed for centuries, tucked away in our holiday traditions so permanently they escape the passage of time.

The holidays are full of these time travel moments. It’s inescapable: you know all the words to Christmas songs from the 40’s, you unearth your grandmother’s good china, you hang that snowman ornament with the worn off glitter from kindergarten, and somehow, bewilderingly, you still untangle and test partially burnt-out strings of lights from Christmases decades ago. Part of the holiday magic, its core appeal, is all that timelessness. We anticipate these hallmark rituals— music, decorations, mementos, heirlooms—and it wouldn’t be Christmas without them. We raise our children to love and expect them, passing them from one generation to the next.

Of all these time capsules, nothing is as powerfully, evocatively resistant to the passage of time as our recipes. Our holiday dishes and drinks can be centuries old. Flavors brought to their fullness in the 18th or 19th century are still delighting us—and sometimes confounding us—well into the 21st. They serve as a thread connecting us to the places and people of our past. Holiday dishes might speak to the heritage or culture of your diaspora, the sauerkraut served alongside the turkey. Preparing and enjoying them is also an act of remembrance, each one a little shrine to the cooks and shared meals of long ago. Eggnog, fruitcake, mincemeat pie, even the ubiquitous pumpkin spice—all are antique time travelers from centuries past that live on in our seasonal winter celebrations, year after year.

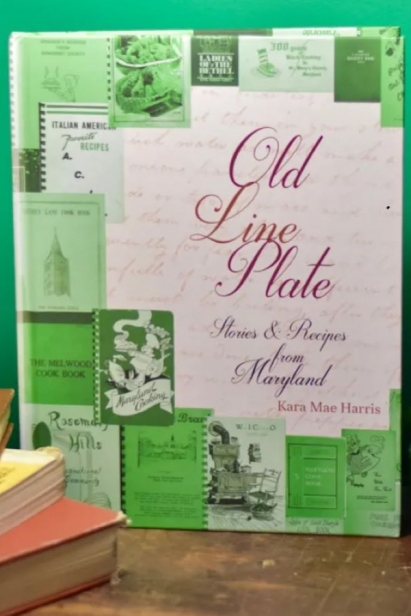

The Chesapeake has its own holiday recipes, some specific to one community, one church, one family. Local cookbooks are full of them, and often the stories behind them, too. That mixture of community history and a sense of place, told through food, is a big part of what draws foodways historian and blogger Kara Mae Harris to collect them. Among the 29,000 old Maryland recipes archived in her database at oldlineplate.com, many that she’s blogged about and taste tested, there are many, many holiday dishes. To Harris, it makes perfect sense that our special Christmas dishes are heavily represented and resistant to the passage of time.

“There’s a quote by (African American foodways historian) Michael Twitty that I really love,” says Harris. “He says food doesn’t have meaning. We give food meaning. But there’s definitely this sense at the holidays that food is giving them meaning. Holidays are about nostalgia and setting a mood with food.”

Maryland’s Way is the first cookbook that Harris started testing recipes from and blogging about. The OG of Chesapeake cookbooks, it boasts all sorts of period holiday dishes from around the state that have survived until today because of their special antique origins. One of Harris’ favorite examples is hard jelly cake. Developed and specific to the community of Shady Side on the West River, it’s a very unique, uber-regional dessert that’s somewhere between a cookie, a grape jelly sandwich, and (in layers if not flavor) a Smith Island cake.

The recipe for hard jelly cake was printed in the first edition of Maryland’s Way in 1966, but it is clearly much older than that. Contributed by Mrs. Edgar Linton, it is described as “an old Southern Maryland receipt, popular at Christmastime. A Shady Side specialty, it keeps very well and looks festive when sliced thin.” Harris found the cake had roots in baumkuchen, a German traditional holiday cake, but the final recipe was the product of time, adaptation, and ingenuity. “Loving traditions will always morph and change to match our resources,” Harris said. “In 19th-century Shady Side it became something simpler, and entirely unique.”

Women from the Shady Side community remembered making hard jelly cake with their mothers, grandmothers, or great-grandmothers, often for bake sales, as gifts or for raffles around the holidays. “Having it be your family recipe makes a cake really good for gift giving,” Harris said. “You’re giving a part of yourself and your heritage to the people you care about.”

Harris took a stab at making the cake herself and found it a little too intensely grape-forward for her liking. Even some of the Shady Side bakers agreed with her there, and suggested elderberry jam as a non-traditional, possibly tastier alternative. At the end of the day, though, the flavor of hard jelly cake mattered less than the process. The ritual of preparing the cake was so important that even overseas cooks found a way to keep the tradition alive, making hard jelly cake from postings in Germany to bring memories of long-ago Shady Side Christmases to life, on the other side of the world.

Holiday drinks can also have surprisingly deep roots in the past. Of course, there’s the ubiquitous eggnog that’s hung on through the centuries, but the Chesapeake has a few of its own traditional tipples. Cherry bounce is a brandy-based drink that George Washington carried with him in a canteen during a trip across the Alleghenies and was served at parties on New Year’s Day by Martha Washington. A regional 18th century staple, Harris found the recipe was alive and well with multiple versions in Maryland cookbooks like Eat, Drink & Be Merry in Maryland and Maryland’s Way.

Her taste testing found it gave a whole new meaning to the idea of “holiday cheer.” Though some historic cherry beverages include low amounts of alcohol for medicinal purposes (like cherry cordial), the high-test version of cherry bounce Harris brewed up in her kitchen suggested this was a social rather than a curative drink. Made with fresh strained cherry juice and cinnamon, lemon peel, and the 18th century spice trifecta of allspice, mace and cloves, the cherry bounce recipe also called for one gallon of brandy to every four gallons of juice. “The cherry bounce was extremely potent,” Harris said. “I guess I don’t consume that much brandy, but it’s extremely strong. The flavor of cherries really concentrates and develops over time.” She laughs. “We mixed it with wine, to try and water it down.”

Harris also gives a shout-out to the apple toddy, which was traditionally Marylanders’ way to make extremely merry—like, brawling-in- the-streets-and-getting-arrested merry. A punch of roasted apples, brandy, rum, water, sugar, and lemon rind, apple toddy was lauded as a taste of the Chesapeake holidays prior to Christmas and bemoaned as a source of hangovers afterwards. As an article from the Annapolis Gazette on December 28, 1854 remarks, “Christmas Day was rightly observed in our ancient city. Judging from appearances, a quantity of eggnog, apple toddy and similar potables must have been brewed and consumed on the occasion. Notwithstanding the “tight” times (in both senses), everybody seemed happy and comfortable. How far this comfortable feeling extended into the next day, we cannot say.”

Cooks were instructed to let their apple toddy mix steep for maximum strength. A recipe from Maryland’s Way recommends preparing it in January for use the following December. The potency of the drink and the subsequent fighting after a couple of servings were seen in the early 19th century as a matter of routine. Harris credits temperance for a big reason apple toddy lapsed into obscurity. She cites an 1873 article in the Baltimore Sun detailing the work of temperance advocates to specifically target the service of apple toddy in private homes over the holidays. Within ten years, apple toddy had already begun to fall out of fashion and with it, the arrests over the Christmas season—as well as a little bit of what made Maryland holidays unique.

For all the bad behavior too much apple toddy could encourage, Harris thinks we’ve lost something quintessentially Maryland without it. “I don’t think anybody’s really making apple toddy, and that’s a shame. I’m basically a non-drinker, but I really want people to do these things. Somebody should bring back apple toddy. It’s such an interesting old Maryland tradition.”

Keeping the past alive is maybe the thing that Harris is most passionate about, along with understanding people and traditions of the past through food. But she’s not hidebound about it. In fact, like apple bounce or hard jelly cake, she encourages the revival of old holiday recipes or the adoption of new ones in the spirit of creating a celebratory feeling.

“Sometimes I think people are a little too hesitant to start new traditions. Try out new recipes. If you make something and somebody loves it, bring it back next year.” Harris’ own family holidays include an old pound cake recipe, distributed lovingly by hand door-to-door, and a relatively new addition of very un-Maryland gravlax. She shrugs. “Family traditions don’t have to be as old as time.”

Kara Mae Harris’ archived recipes (including the ones mentioned here), foodways history and experimentation with old Maryland recipes can be found on her blog at oldlineplate.com.