Precious Metal: Butter Pat Industries

When a bowl breaks in Japan, it is not always thrown away. In fact, for some 500 years, the pieces have been picked up and put back together through the ancient art of kintsugi. The cracks are not hidden but rather are celebrated, repairing the broken pottery with a lacquer of gold, and imbuing this otherwise ordinary object with not only new life, but meaning.

A world away, that sentiment has been a source of inspiration for Dennis Powell of Butter Pat Industries in small-town Easton, Maryland. In 2013, he dropped the old cast-iron pan of his grandmother, Estee— “overwhelmingly the most influential person in my life,” he says with a slight Southern drawl—but it wasn’t until that thick, black cast iron laid in half before him that he realized its true value. “When something is so much a part of you, it doesn’t seem special,” he says. “But that pan was like my right hand. I used it every day.”

Telling the tale of Japanese kintsugi is just one of Powell’s many “shaggy dog” stories, as he calls them, leaning back in a chair at his Talbot County office before diving into the next one. They’re a good window into the mind of this former architect and sort of mad scientist who’s crafting some of the country’s coolest cast iron. “I’ve always been fascinated with the way we take something as simple as a frying pan,” he says, “and then suddenly, because we call it an heirloom, we make it valuable.”

Powell is interested in these kinds of connections—in how things fit together, in how they came to be in the first place. At first, for him, the plan was to simply repair the pan to pass on to one of his sons. He already knew a thing or two about cast iron, having been collecting and reconditioning old pans to accompany the outdoor fire pits of his good friend’s Cowboy Cauldron Company. But in this new quest, he soon discovered that the molded metal is simply not made the way it used to be, at least not in America. Which inspired him to ask: why not? And better yet: what’s stopping me?

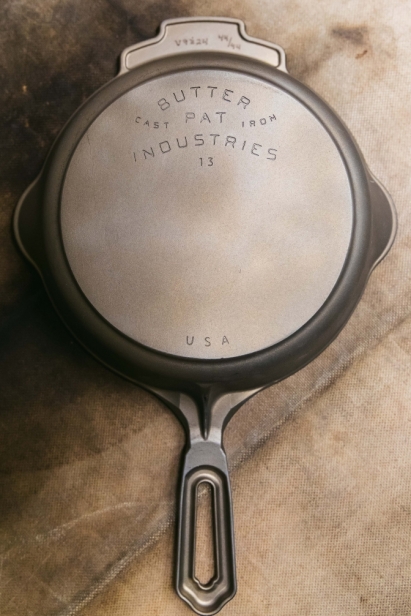

Over the next several years, Powell set out to create his own cast irons—less like Lodge’s hallowed yet hefty cookware, and more like the smooth, lightweight products of the early 20th century, which are now coveted by home cooks, star chefs, and antique collectors alike. On the shelf beside his desk he keeps a couple of examples, which he’s toted over the years to naysaying foundries. Most dismissed his desired specifications as something that couldn’t be done, and even after one Pennsylvania foundry finally gave him a shot, it would still take many months and dozens of failed prototypes before they found the perfect recipe. “We were about to give up,” says Powell. “Then I got a photograph from the guys at the foundry of a pan on the furnace, cooking hamburgers.”

In the spring of 2016, the first Butter Pat was born—the Lili—and before long, three more skillets would come online in varying sizes—the Joan, the Heather, and, last but not least, the Estee—all named after women who influenced the men who made them.

In that same Lancaster foundry, each pan now takes about 21 days to make, and in those three weeks, Butter Pat is working not just to bring the old-school kitchen tool into the 21st century, but also to reignite the fading concept of American craftsmanship, with literal fingerprints sometimes finding their way into the iron surfaces. The final products are then seasoned and shipped out of their Maryland warehouse, near which Powell lives with his wife, Matilda, and their American water spaniel, Trix.

Though a South Carolina native and longtime D.C. resident, Powell had been coming to this slice of Maryland for decades, seeking out the tidewater terrain for its big-city respite before renting a house on the Choptank River, where he brought—and broke—Estee’s pan. “The Eastern Shore gets in your blood,” he says, now owning his own home here and relishing time spent outside, cooking soft-shell crabs over a live fire or partaking in the region’s renowned waterfowl hunting. “We’re not sailors, we’re not motor boaters. We just love the rural lifestyle of the Chesapeake.”

But even after all his hard work, Powell is not yet ready for retirement. He still finds himself dreaming up new designs and examining each pan before it heads out the door. And after two short years, his products have already landed in the hands of lauded chefs, such as Sean Brock of Husk in Charleston and Spike Gjerde of A Rake’s Progress in D.C., as well as the test kitchens of magazines like Food & Wine, Martha Stewart, and Bon Appétit. Home cooks can find them online, as well as occasionally on sale during the warm-weather farmers’ market in Easton.

The price might seem high, ranging from $145-395, but Powell insists that his pans are meant to be used every day—to fry eggs on the stovetop, to roast vegetables in the oven, to grill wild oysters over an open flame. As utilitarian as they are upscale, as finely crafted as they are functional, “I don’t want people to reserve them solely for special occasions,” he says. “I always tell people, just cook anything in them—tonight!”

Besides, each Butter Pat is likely to last longer than any one lifetime. “For me, being an artist, I can only hope that 100 years from now, someone is going to pick up one of these pans and look at the shape, at the way it was made, and appreciate this object,” he says, “much in the same way that the Japanese do.”

Each pan has creating the potential to become, Powell hopes, just as precious and priceless as Estee’s. Still, try not to drop it, even if the golden scars are beautiful.

Butter Pat Industries, 29000 Information Lane, Easton, Maryland butterpatindustries.com