Millions of Peaches: A Delmarva Legacy

Photos from the Library of Congress and the Maryland State Archives.

Chesapeake summer has a soundtrack. It’s the drone of distant outboard motors, the osprey’s chirping call as it circles, looking for a fish dinner. It’s the clang of the big aluminum steam pot, the scrabble of claws inside as blue crabs meet their delicious demise. Crickets and bullfrogs keep a steady tempo deep into the summer nights. And on really special occasions, maybe for a 4th of July party or a family reunion, you can hear a distinctive grinding crunch—the clarion call of hand cranked ice cream.

The racket of the ice cream maker at a family gathering last summer might as well have been a one-way ticket on the time travel express. I was immediately transported to the summers of my childhood, when my maternal grandparents treated their pack of barefoot grandchildren to bowls of milky ice cream laboriously cranked by hand. It was a tradition handed down from my great-grandfather, “Bubba,” a man known for taking great pleasure in delighting small children. Bubba’s recipe, which became my grandmother’s, was nothing like the bubblegum or rainbow sorbet flavors of 80’s era Baskin Robbins I was used to. A few simple ingredients plus the amazing alchemy of ice and salt created a refreshing, lightly sweetened ice cream. It was the perfect foil for Bubba’s favorite star of the show—luscious local peaches he’d source from nearby Godfrey’s Farm in Sudlersville, Maryland.

The whole passel of grandkids would hover around the ice cream maker, which was as good as a tv show for its entertainment value. When my Mom-mom deemed the ice cream firm enough, we’d line up with bowels extended. Dollops of the rapidly melting ice cream were dished out. You ate the golden lumps of ripe peach swimming in a sea of frozen cream wordlessly, scraping down the sides to get every last bit. It was summertime in a bowl.

As with so many culinary traditions here on the Eastern Shore, Bubba’s peach ice cream has roots in the past. It’s a taste of the era of Delmarva’s vast orchards—a 50-year period in the late 19th century when railroads and packing houses capitalized on the region’s enormous arable acreage. Farms that were once dedicated to tobacco and wheat now grew produce—tomatoes, watermelon, berries, peaches—to be picked, packed, and shipped during summer canning season.

Summer produce like peaches went hand-in-hand with the region’s seasonal winter oyster harvest. Fruit and vegetables were transported along the same railroad, steamboat, and skipjack routes, and were prepared and packed in waterfront canneries that proudly advertised canned produce alongside their winter offerings of fresh and spiced cove oysters. Like Chesapeake oysters, canned Delmarva peaches were exported hundreds of miles by rail to the furthest edges of the country. Their golden halves, floating in syrup, represented a taste of home and a seasonless luxury to pioneers at frontier outposts.

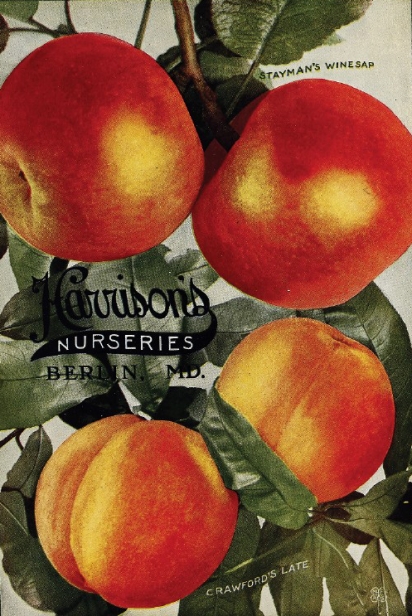

The demand for a summertime treat out of the growing season was bottomless. Peach orchards soon covered huge swaths of Delmarva’s countryside, replacing other staple crops like wheat as farmers invested in the fad for canned peaches. Nurseries like Harrison and Sons in Berlin, Maryland, offered farmers several dozen varieties of peach trees, recommending the Elberta and Brackett varieties as particularly suited for commercial production. Of Elberta, their 1890 catalog states, “Their fruit is large to extra large, golden yellow, with brilliant shades of red; firm, juicy, rich, sweet.”

Elberta, Brackett, Hiley Belle, Eclipse, Mountain Rose—orchards of different varieties stretched for miles alongside dirt roads that reached into the heart of Delmarva. Whole communities like Middletown, Delaware and Berlin, Maryland were built on peach profits, their downtowns full of ornate cupolas and Victorian latticework—the highly ornamented temples of the peach economy.

Of course, peaches are grown to be eaten—and the pinnacle of the peach in the late 19th century was celebrated in a million different peach recipes. Brandied peaches, peach cobbler, peach pound cake (also with brandy, why not?), Baltimore peach cake, peach pie, peach preserves—home cooks found all sorts of new, innovative recipes for delicious canned peaches. My great-grandfather grew up at the end of this peach renaissance. As a child in Sudlersville, Maryland, he was raised in the heart of Delmarva’s peach country. Early and frequent peach feasts fostered a lifelong love. Even as an adult, sugared peaches in cream remained his favorite summertime breakfast, a tradition he shared with my mother and her siblings when they were small.

Looking back, it seems entirely natural that hand-cranked peach ice cream is a part of my earliest, most fledgling food memories. As an Eastern Shore native and a descendant of a generation fed, housed, and employed in part by peaches, that golden ice cream was practically a birthright. On the other hand, how could I have known how seminal that flavor really was? By the time of our backyard cookouts, the Eastern Shore’s peach orchards were long gone.

The late 19th century saw a proliferation of "peach yellows," a phytoplasmic microorganism spread from wild plum trees by leaf-hopper insects. Somewhere between a virus and bacteria, the yellows caused premature ripening of the fruit, which became bitter and inedible. In a time when Pasteur’s recent 1857 discovery of microorganisms was cutting-edge science, peach yellows confounded farmers and scientists alike, who speculated all sorts of causes for the blight—grubs in the roots, mildew, fungus. There was vigorous debate about the best solution in the comment section of every newspaper on the peninsula. Apply more manure at planting. Coat the roots with ash at the beginning of the season. Of course, without pesticides, all proposed solutions failed. Within 20 years, Delmarva’s magnificent peaches—and the world that flourished with them—were gone, uprooted and plowed under.

Today, the signs of peach prosperity linger if you know where to look. The old road into Middletown—now mostly hidden beneath housing developments and distribution centers—was once a long march of fine peach plantations with massive columned homes and stately trees. A few holdouts are still there, and Middletown celebrates a peach festival every year in honor of its peach heyday. And giving Georgia a run for its money, Delaware’s state flower is the peach blossom.

Over the state line in Maryland, Berlin still holds an annual peach festival, and Sudlersville—Bubba’s hometown—has one each year, too, in early August. Peaches have proven a tenacious, delicious guest of honor in our Delmarva parties and recipes, even if the reason we celebrated them in the first place has grown a bit cloudy.

Which gets me back to peach ice cream. Thanks to the wonders of the internet, you can adopt peach home-made (if not hand cranked) ice cream as your new/old family tradition beginning this season. With the investment of $45 for Amazon’s top-rated electric ice cream maker and the world’s simplest ingredients, you can pick the most beautiful, blushing peaches at your farmer’s market or favorite shop and give them the treatment they deserve. A quick skinning and chopping and you add the peaches to a rich base of milk, cream, sugar, and eggs. Let it chill for a few hours and you’re ready to churn. After 20-30 minutes of enjoying the sound but not the labor of ice cream, it’s ready. Decadent, lush, in the bowl or on a cone, peach ice cream is the timeless taste of Delmarva’s summer—whether 100 years ago or this very afternoon.