The Most Savory Shad: Delmarva's Taste of Spring

In the Mid-Atlantic winters of generations past, the bitter end just before spring was a time of scant menus and empty larders. Gone were the put-up summer produce and the dried fruits of the holiday season. Even hardy cold-tolerant staples like potatoes and winter greens were picked over and frozen in the frost-ravaged ground. But while the green bounty of spring was still at least a month away, salvation was imminent. Pulsing up the chilly rivers like a silvery life force were fish—millions and millions of fish. Alosa sapidissima, the American shad. Ocean-dwelling schools of immense size returned to the rivers of their birth every spring to spawn in the headwaters, spelling relief and sustenance for all along their watery route. Their flesh and their roe were devoured by hungry river communities where the taste of shad, fatty and restorative, defined the spring season.

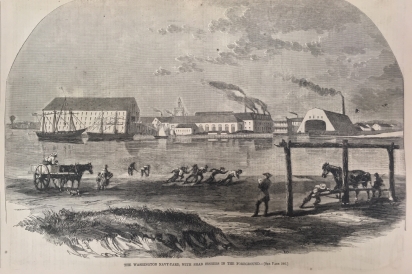

American shad is one of six herring species native to the rivers of the East Coast that return to their natal streams to spawn. American shad, the largest and the most delicious variety (sapidissima literally translates to ‘savoriest’), historically comprised one of the spring’s most important seasonal fisheries, especially along the Chesapeake Bay. Harvested simply, with nets and small skiffs, shad in the millions were landed at waterfront estates like George Washington’s Mount Vernon where they were filleted, salted and packed by slaves in an international fishery that reached as far away as the Caribbean. Even today, salt fish persists as an important element of Afro-Caribbean foodways—a holdover from the days when salted shad from the Chesapeake was a ration distributed to slaves on sugar plantations.

Although shad were easily preserved by salt, their flavor was fullest when the fish was eaten fresh. Shad are an oily, bony fish that can be challenging to eat if not properly prepared. But in the millennia that humans have been consuming shad along the Chesapeake and Delaware river watersheds, simple, timeless recipes were developed to prepare the succulent flesh and meaty roe.

Take, for example, the technique of planking shad, a radiant cooking method that’s persisted since before colonization. In this approach, cleaned, gutted shad are applied skin-side down to a hardwood plank, sprinkled with salt, and held in place with nails. Then, the plank is arranged near—but not too near—a bed of coals and left to cook slowly. In this way, the shad’s many bones gradually disintegrate in the radiant heat from the fire, while the fire’s smoke gently permeates the fish. It’s a deliciously simple way to prepare shad, and one that can cook many shad at once. In the 19th century, shad planking became synonymous with community spring suppers—especially ones sponsored by politicians looking to curry favor with by filling lots of bellies during their stump speeches. To this day, Virginians still associate the term ‘shad planking’ not with eating fish but with springtime political rallies.

Some shad preparation methods transcended regional obscurity. For generations, shad roe was a lauded and greatly sought-after East Coast springtime treat. In the 19th and 20th centuries, after salted shad fell out of favor, the flavorful, delicate roe was the primary catalyst behind the large-scale harvest of shad between February and May on regional tributaries. Shad roe, stored in two large lobes known as ‘sets,’ has a savory flavor profile similar to sweetbreads. Carefully and gently prepared in order to keep the sets intact—with their millions of tiny eggs inside—shad roe was a delicacy lauded by gourmands and home cooks alike.

The most common Chesapeake recipes called for lightly sautéing the sets in butter in a heavy skillet over low heat. Turned carefully to allow for even cooking and to prevent the eggs inside from exploding, the roe was gently browned and served with a little browned butter and a side of scrambled eggs or bacon as a breakfast dish. For a slightly more elevated preparation, the shad roe could also be marinated in lemon juice and olive oil with a bit of minced onion, parsley and salt and pepper, then broiled until browned and served with a lemon, chive and butter sauce.

From the 1800’s to the 20th century, these simple, flavorful dishes of roe were hotly anticipated every spring season, and fishmongers and fine restaurants along the East Coast proudly announced the imminent arrival of roe on their menus once the shad runs started. But overfishing and the construction of dams throughout the Chesapeake’s tributaries took their toll on the once-mighty shad populations. Numbers of shad began to dwindle precipitously in the 1920’s, prompting the states of Maryland and Virginia to begin early population restoration efforts. Despite their best attempts to stock more shad, remove dams or install fish ladders, ultimately the Maryland fishery declined so dramatically that the commercial harvest was closed in 1980, and Virginia’s followed suit in 1994.

Fortunately for the shad—and shad roe lovers—the Delaware River was never dammed. Today, thanks to a small but steady shad population, the Delaware River is one of the few East Coast tributaries that permits the commercial harvest of shad—a boon to Delmarva residents eager to savor the taste of spring, for the first time or as a beloved traditional staple. For those looking to get their fill, Northeast Seafood Kitchen in Ocean View, Delaware, serves the roe over crostini, drizzled with a garlic and caper brown butter sauce, while Feby’s Fishery in Wilmington, Delaware offers roe-loving home cooks the chance to get their hands on a few fresh sets during the season. Whether tenderly prepared by a professional or carefully cooked at home, don’t miss shad roe—the quintessential taste of Delmarva spring—on your seasonal table.