Farm to School: William Penn High School Connects Students to the Land

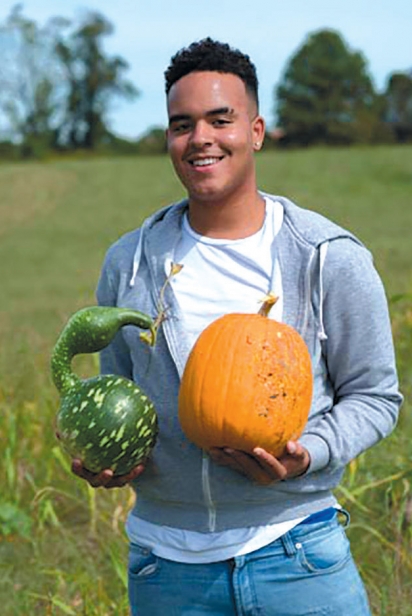

When Christian Sledge gazes down into the crate of freshly picked peppers by his feet, the 17-year-old envisions salsa.

“Or pureed in a sauce,” he says. The orange habaneros catch his eyes, mixed in alongside green Anaheim chilis and cubanelles. “I love spicy foods,” he says. “I love touching peppers, tomatoes, getting my hands dirty. My classmates are eating our food, so I’ve got to make it the best I can make it.”

Sledge and a handful of his classmates from William Penn High School are sitting on six acres of tranquil farmland in New Castle where together they sort through bushels of mixed peppers, which were picked by a different group of students just minutes earlier.

Aside from a few errant giggles, the teenagers work quietly in the late summer sun. Chickens cluck in the background. The hum of traffic from Dupont Highway seems distant.

Welcome to Penn Farm, a 300-year-old farmland once owned by William Penn himself. Today, the young people who tend to the fields, the soil, the bugs, and ultimately, the food, have carved out their own mini ecosystem just minutes from the pavement and strip malls of New Castle.

Thanks to seven years of momentum and some truly impressive cross-pollination, the farm is yielding fresh, hyperlocal produce that fuels a culinary powerhouse at the state’s largest public high school.

Kathleen Pickard, an agriculture science teacher at William Penn, was there at the beginning when a patch of land on the long-time tenant farm was granted to the school by the nonprofit Trustees of The New Castle Common. “There was a meeting,” Pickard says, “and next thing you know we were out here farming.”

William Penn’s U.S.D.A.-endorsed “Farm to School” program connects three Career and Technical Education areas (or “majors” that the school offers to students): environmental science, culinary arts, and agriculture. By entwining the once-siloed disciplines, students in each one receive a holistic perspective of the entire agricultural life cycle from seed to plate. Faculty members collaborate to ensure the entire system runs as efficiently as possible, and that students receive all-inclusive learning from each department.

This means back in the school kitchen freshmen like Brytany Finner get to rinse off the veggies she helped grow, and transform them into seasonal dishes for the school’s cafeteria, or for the school’s Penn Bistro for faculty and VIPs, or at local catering gigs. “It’s important to me, knowing where my ingredients come from,” says Finner, 14. “If I’m cooking for somebody, I want the freshest food to give to them.”

It’s no wonder culinary teacher Kip Poole has molded this program into one of the state’s true cooking juggernauts. This past spring the school’s culinary and management teams each won first place at the fifth annual Delaware ProStart Invitational, fending off 12 other teams from high schools across the state to advance to the national finals in Charleston, S.C. They bring home hardware at nearly every local foodie event around—nabbing first overall at the Farmer & The Chef competition in 2015 and 2016 with dishes like chicken roulade with chorizo, squash, black garlic, and miso-cured eggs, or pumpkin-espresso panna cotta. They work private catering events and donate to local food banks. Their graduates regularly join the ranks of Johnson & Wales or the Culinary Institute of America.

“It’s a blessing and an honor to wake up and go to a school that has such a unique and incredible environment,” Poole says. “We’re doing something that very, very few people in the country are doing. And the kids honestly understand what they’re cooking, which is amazing. I have students in my class that placed the seed in the soil, watered it, harvested it, brought it into the kitchen and we cooked it.”

Poole points to the emergence of the farm-to-table movement and heralded restaurateurs like New York’s Dan Barber—who blurs the lines between dining and agriculture and the experiential and educational—as contributors to William Penn’s momentum. But few are doing farm-to-table at the high school level.

“I’m not being pompous,” says Poole, “But I’m saying that because of a lot of drive and passion from the school, we are turning this into a dream for us and community. What we’re doing is only going to make every culinary and every ag program in Delaware bigger and stronger. I think we’re going to see this everywhere. People are finding out about this tucked-away thing and I want to keep it going. I want bless the whole state and teach them how we can all do this.”

For all the sizzle Poole’s army of chefs can conjure, the humble and earthy agriculture team are the heart of the operation. A love of farming didn’t stir in suburban teenagers overnight, but under Pickard’s guidance, plant science classes jumped from 75 students to 150 in the past year, with animal science classes growing by the same rate.

Eighteen-year-old Nicole Webb says she knows the farm like the back of her hand. She’s been coming here every year (plus summers) since she was a freshman. “I had Plant Science 1 with Ms. Pickard,” she says. “It wasn’t my career field but I got put into that class, and I’m so grateful because it helped me figure out what I do with my life.”

Students like Webb, who’s attending Wilmington University this semester in hopes of becoming an agriculture teacher herself, say they’d rather learn outside than from a chalkboard. “I like the uniqueness of this place. You’re on a historical landmark, and everything is just so pretty. From when you plant seedlings to when they grow big, the whole environment is just amazing.”

The adults running the show get swept away too. Scott Schuster, who serves as a nutrition outreach specialist for the Colonial School District, works with the school to funnel the food that the farm produces into school lunches while working with a dietitian to write menus. He also writes grant applications that have helped grow and strengthen Penn Farm and provide even more opportunities for students. A $100,000 grant from U.S.D.A in 2014 allowed the school to purchase equipment, infrastructure needs, seeds, and the salary for farm manager Toby Hagerott.

“A lot of our young people today have no connection to where their food comes from. We ask kids before we start, and they say the supermarket.” Schuster says. “But seeing a kid pull a carrot out of the ground for the first time is probably the most liberating, profound thing. It’s incredible.”

Witnessing those a-ha moments are a big part of the fun, Hagerott says. And the tangible, communal nature of farming, he says, zaps teenagers’ brains in a way that smartphones simply can’t. “They’re doing something meaningful,” he says. “They see their hard work at the end of the cafeteria line and say, ‘Hey, I harvested those tomatoes. I planted those squash.’ You see that click. They may hate to pull weeds, but they have fun doing it with a group of their friends.”

Penn Farm practically transformed the lives of the Brellahan family. Mom Mandy watched as a fledgling interest in animals grew into a passion for her daughter Morgan, who joined the school’s 4-H club after her first visit to the farm. Son Hunter is part of the school’s culinary program. Today Morgan is dreaming of a career as a conservationist or a zoologist, while Mandy gets to enjoy life at home with a clutch of live chickens. “The kids still have their computers, their gadgets, but working on a farm has made them a lot less lazy,” she says. Accompanying a group of Penn Farm students to the Delaware State Fair, Mandy watched as the young agrarians woke up each morning at 5 a.m. to show and care for livestock and crops, heading to bed each night around midnight for 10 days straight. “There was not one complaint,” she says. “It was amazing to see the responsibility these kids had acquired.”

The good vibes don’t end there. Nearly all of the school’s departments have woven their way into Penn Farm in one way or another. Environmental science students help monitor and maintain the ecosystem’s overall health—testing soil, hunting for insects, or planting native plants for the school apiary’s bees. English as a Second Language students visit the farm’s resident animals to learn linguistic concepts like body parts, animal names, or verb tenses. Students involved in health services studies might check the animals’ pulse rates. And the Penn Farm roosters have become popular models for the art department. “We see our social studies students, archeology, history, English teachers—you name it,” Pickard says. “Studying a poem about plow-shares? Well then come down here and see what a real one looks like.”

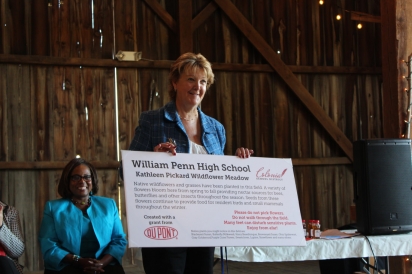

The Penn Farm bandwagon is filling steadily. This spring, one of the state’s most prominent employers, DuPont, surprised faculty with a $5,000 grant during an awards ceremony. The money will be used to enclose the farm’s apiary in a clear encasement to allow students to study the beehive’s activity safely. Months later during Agriculture Education Awareness Day, leaders gathered on the farm to dedicate an adjacent wildflower pollination field. They named it after Kathleen Pickard, the school’s first and foremost cross-pollinator. “I was awestruck,” Pickard says.

As fall transitions to winter and the farm begins to shut down for the season, elements like the apiary and a new aquaponics system—where goldfish and tilapia live and provide nutrients to hydroponically grown produce—provide an added value. The last of the cabbages, kale, fennel, broccoli, tomatoes, and winter squash are harvested, broken down, and served or flash frozen for later.

It’s a bittersweet time for young farmers like Nicole Webb. “The remaining plants die and return to the ground, the cornfields start to go back to seed, and the leaves start to turn, it’s really pretty,” she says. “Still, I’d rather be outside learning than inside staring at a chalkboard.”